Promising results of first-in-human trial

ACL reconstruction surgery is one of the most common orthopedic procedures in the United States. The procedure, which involves removing the torn ACL and grafting in a piece of tendon from elsewhere in the knee, restores knee stability. However, current research suggests that 76 percent of patients with an ACL tear develop osteoarthritis within 14 years of the original injury, whether or not they have reconstruction surgery.

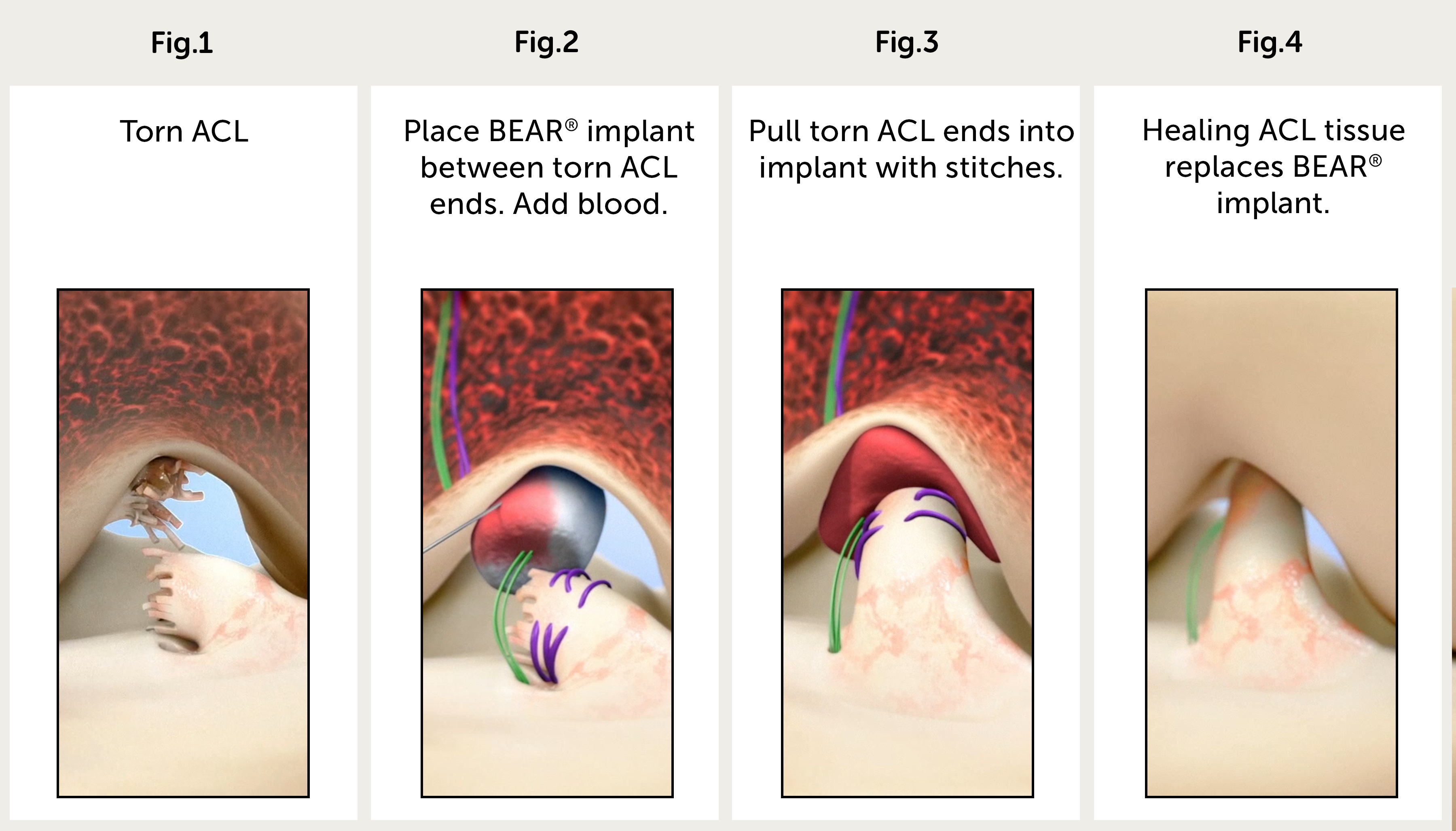

In an effort to improve patient outcomes, we developed a method of regenerating torn ACLs rather than replacing them. The Bridge-Enhanced® ACL Restoration (BEAR®) procedure is a suture repair of the ACL combined with a specifically designed extracellular matrix scaffold that bridges the gap between the two ends of the torn ligament. In animal studies, the procedure appeared to prevent later development of osteoarthritis, possibly because the regenerated ligament more accurately restores the anatomy of the original joint compared to reconstructing the ACL with a graft.

Stages of bridge-enhanced ACL restoration

Promising early results for new ACL surgery

In an article in the Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine and in a presentation at the Arthroscopy Association of North America (AANA)/American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine (AOSSM) 2019 Specialty Day, we reported the 24-month results of our phase I, FDA-approved, first-in-human study assessing the safety and early efficacy of the BEAR procedure.

The study, led by orthopedic surgeons Martha Murray, MD, and Lyle Micheli, MD, began in 2015. Of the 20 patients who participated, 10 underwent the BEAR procedure and 10 received standard ACL reconstruction. All of the subjects were between the ages of 18 and 35. Nine of the 10 subjects who received BEAR surgery and 7 of the 10 subjects who received traditional ACL reconstruction completed a 24-month study visit, which included an MRI.

The two groups had similar clinical, functional, and patient-reported outcomes, with significant gains over baseline preoperative values. At 24 months, all 9 patients in the BEAR group exhibited continuous tissue in the region of the ACL. Similarly, the ACL grafts were intact in all 7 patients in the ACL reconstruction group who returned for follow-up, with no gap between the proximal and distal limbs. The only difference between the two groups at 6, 12, and 24 months after surgery was significantly greater return of hamstring strength in the BEAR group.

ACL Study | Safety first

This phase I study was the culmination of 15 years of laboratory work developing a safe and effective scaffold. In unrelated studies conducted at other research centers, 20 percent of subjects had a serious inflammatory response to other extracellular matrix patches. With this in mind, we designed our phase I study with a small sample size to screen for problems that might occur in a larger study. Happily, none of the subjects who received a BEAR implant developed an infection or severe inflammatory reaction, arthrofibrosis, or reaction that required scaffold removal.

We are now conducting a randomized, blinded trial with 100 patients to compare the outcomes of the BEAR procedure with those of standard ACL reconstruction. We started enrolling patients in May 2016 and completed enrollment in June 2017. We have implanted more than 100 BEAR scaffolds with no sign of infection. We expect that two-year follow up data will be available later this year.

A third study, BEAR III, has enrolled 49 subjects at two sites, Boston Children’s and Rhode Island Hospital. We have expanded the age range of this study to include patients between 12 and 80 years old. We anticipate enrollment for the BEAR-MOON study, a five-site multicenter study led by Kurt Spindler, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic, will begin later this year.

Areas of future research

The apparent safety of the scaffolding, combined with these early results, suggest that even in this first-in-human study, the BEAR procedure is comparable to ACL reconstruction in terms of knee stability. Future studies could test whether patients experience less loss of strength following surgery and if patients have better function and less posttraumatic osteoarthritis for decades after the procedure. The BEAR procedure has the potential to serve as the basis for less invasive, more effective procedures for patients with torn ACLs and other musculoskeletal injuries.

Murray, MM, Kalish, LA, Fleming, BC, Flutie, BM, Thurber, L, Freiberger, C, Henderson, R, Perrone, GS, Proffen, BL, Ecklund, K, Kramer, DE, Yen, YM, Micheli, LJ, Bridge-Enhanced Anterior Cruciate Ligament Repair: Two-Year Results of a First-in-Human Study, Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine